Urban Environmental Justice: Green Spaces

By Delilah Hernandez

One time during class, my professor had us look over data tools that graphed green areas and pollution zones around Chicago. At the time, we were learning about Little Village and the fight to close down a coal-burning power plant that was the lead source of air pollution in the area. Because the power plant was in the heart of the neighborhood, community members, especially kids and the elderly, were at increased risk of developing illnesses if they lived or worked near the plant. Asthma became the most common illness for kids to develop in the neighborhood, and it was clearly due to the fact that the power plant was emitting tons of air pollution right into a predominantly Latinx neighborhood.

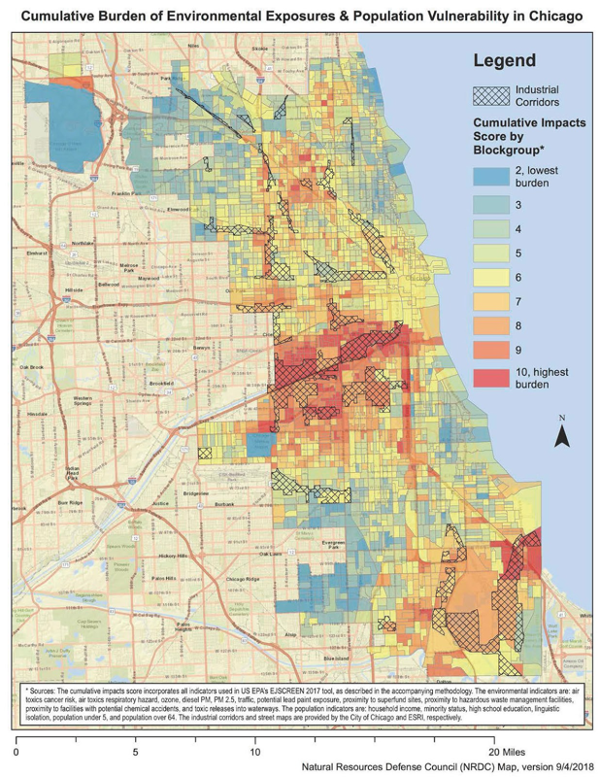

As I was looking through the map, I noticed countless clear green spots on the east and north side of the city. However, in the west and south sides, green areas were lacking. During high school, I would accompany my mom in her nanny jobs and they were almost always downtown. I recognized those same areas in the map. I walked through them and saw the gardens and large green areas with people walking their dogs. Those areas made me feel calm and safe. On the other hand, walking through my neighborhood, especially after sundown, was never an option. I lived mostly on the west side and it was clear that these areas had fewer sidewalks, fewer trees, and fewer people outside. Where I grew up, it felt odd attempting to walk around the neighborhood.

Living in a large city, and one that has a rep for being segregated, made me realize how living just 30 minutes apart makes all the difference in how someone grows up.

Low-income and marginalized communities lack investment from the government and other entities, causing massive lifetime negative repercussions. For example, the reason why so many people of color and low-income people don’t know how to swim or bike is because there is no access to public spaces that would encourage kids to pursue this skill. I, for sure, don’t know how to swim other than doggie paddle, but because I am now afforded the tools to learn this valuable life skill, I will end up learning.

The majority of communities of color and low-income people still don’t have the right to accessible green spaces. Such spaces are necessary to form communities and encourage outdoor time which has been proven to help people’s mental health and well-being.

Environmental racism isn’t just looking through a macro-level lens, but looking outside our windows and knowing what factors contribute to the state in which we live in and how that is either disadvantageous or advantageous and why.