Healthcare Insights: Who Will Stand for Patients and How?

By John August

We are all patients, or will be.

Among the most common concerns we have about our experience as patients include: do we have easy access to high quality care; how can we endure increased costs in insurance premiums, deductibles, and co-payments; why do we experience long waiting times, and why are we too often disappointed in the overall experience that we have when we are being treated?

The jury is in about our collective and individual experience:

“Americans' positive rating of the quality of healthcare in the U.S. is now at its lowest point in Gallup’s trend dating back to 2001.The current 44% of U.S. adults who say the quality of healthcare is excellent (11%) or good (33%) is down by a total of 10 percentage points since 2020 after steadily eroding each year.” Between 2001 and 2020, majorities ranging from 52% to 62% rated U.S. healthcare quality positively; now, 54% say it is only fair (38%) or poor (16%). lowest point in Gallup’s trend dating back to 2001.

So…who will stand for patients and the rampant and growing dissatisfaction with their healthcare?

Shall we wait for government/public policy solutions?

While most Americans believe or hope for meaningful healthcare reform, we have experienced little positive reform since the revolution that was Medicare in 1965. The Affordable Care Act passed in 2010 and implemented in 2014 extended healthcare coverage. However, dissatisfaction with healthcare experience in the U.S. stands at a 25-year high!

Runaway cost and diminishing health of our population continue unabated.

What to do?

The great under-resourced and under-supported healthcare workforce could be a big part of the path to transformative improvement for all of us.

It seems obvious that the healthcare workers of the U.S. who provide care for us are the ones who know how to improve many aspects of the availability, quality, and cost of care. My many years of experience in organizing and representing healthcare workers certainly confirms this. It is rare indeed that I have ever met a healthcare worker who in their own words, “was not there for the patient.” Just as common is the complaint from healthcare workers that they are rarely consulted or asked to be involved in the improvement of healthcare. Much of their experience is to go home after their shift, exhausted and frustrated that they were not able to do their work to the patients’ or their own satisfaction.

There is increasing urgency to improve care and reduce its cost.

Dr. Robert (Robbie) Pearl, who I worked closely with at Kaiser Permanente when he led the largest medical group in the nation (The Permanente Medical Group of Northern California), has recently written in Forbes Magazine a concise statement of our healthcare crisis:

“Harvard psychologists Daniel Simons and Christopher Chabris ran a now-famous experiment in the late 1990s. They showed students a short video of six people passing basketballs and told them to count the number of passes made by the three players in white.

Halfway through the film, a person in a gorilla suit walks into the frame, beats its chest and exits. Amazingly, half of viewers — both then and in multiple recreations of the study — never notice the gorilla. They’re so focused on counting passes that they miss the obvious event happening right in front of them.

The authors call this “inattentional blindness.” And you don’t need to visit a research lab to see it. It’s everywhere in American healthcare.

Policymakers, business leaders and medical societies are all busy counting their own pass equivalents: metrics like insurance subsidies, premiums and enrollment numbers.

These details matter but they miss the larger issue: medicine’s invisible gorilla. That gorilla is the $5.6 trillion our nation spends on healthcare each year, a figure that exceeds the total economic output (GDP) of every nation except the U.S. and China.

As a country, we need to stop counting passes long enough to observe how the gorilla negatively affects people everywhere: in Washington, in boardrooms, in workplaces and in rural communities. Only then can we confront the gorilla head on”.

Dr. Pearl argues that certain goals be established through new financial and organizational systems:

- Prevention is rewarded, not ignored.

- Chronic diseases are managed earlier and better, before complications develop.

- Care shifts to the most effective, efficient settings, including centers of excellence and low-cost, convenient virtual platforms.

These principles form the basis of Value Based Care.

There are many health systems which operate under this system, including Kaiser Permanente. In order to successfully implement and sustain such a system requires that the entire management, physicians, and workforce transform the way they work.

The outstanding performance of the Kaiser Permanente Labor Management Partnership (LMP) operating in a system of Value Based Care is the largest and most successful example we have of how the largest enterprise-based workforce in the nation has been mobilized to consistently excel at delivering high quality and affordable healthcare.

How does this happen?

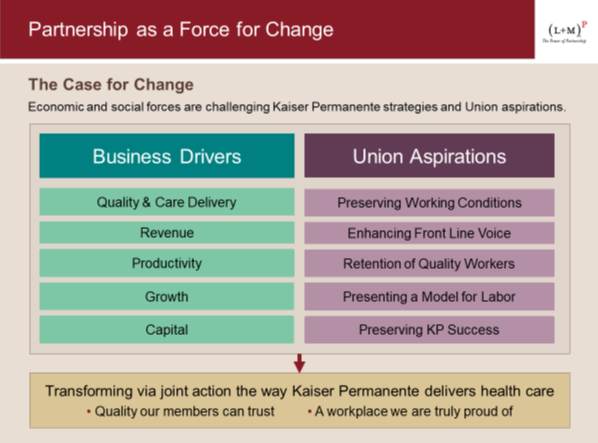

The LMP takes a systems approach to care based on what is best for the patient:

The Value Compass is a central strategy of the Labor-Management Partnership (LMP) at Kaiser Permanente. It was developed through dialogue under the auspices of the LMP between union leadership, health system operational leaders, and organizational design experts.

It was introduced to the workforce in 2007 and has remained the guiding strategy for the organization which includes more than 135,000 union members, 20,000 physicians, all managers and supervisors. The health system cares for 13 million patients every year. The enterprise is among the largest health systems in the country and has the largest unionized workforce in the healthcare industry.

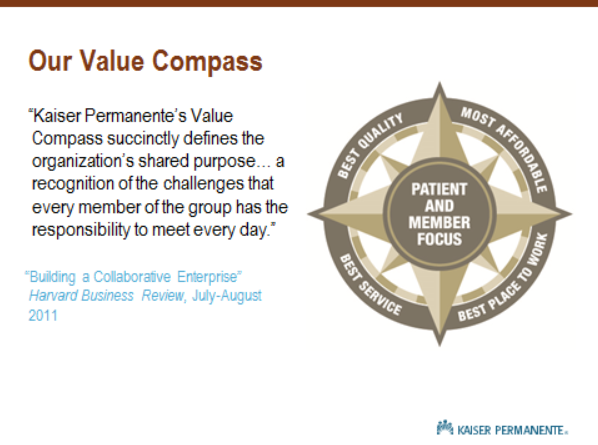

The Value Compass, its implementation, and success is derived from the foundational commitments made between the unions and Kaiser Permanente Leadership through dialogue and interest-based collective bargaining. The result is that traditional and separate interests are embraced as mutual:

The Value Compass is a national strategy based on these mutually held interests, and lives at the frontlines of care where it is implemented through 3500 unit-based teams.

The teams are interdisciplinary made up of nurses, technicians, clerical staff, environmental service workers, dietary aides, pharmacists, physicians, bio-medical engineers, social workers, laboratory, imaging, and operating room staff, indeed a complete cross-section of the healthcare workforce.

Kaiser Permanente has evolved during the same period of the LMP (1997-present) as among the highest performing health systems in the nation. Here is a November, 2025 report on Kaiser Permanente quality:

The report indicates that:

The Healthcare Effectiveness Data and Information Set (HEDIS) is one of health care’s most widely used performance improvement tools. More than 235 million people are enrolled in plans that report HEDIS results.

This report shows Kaiser Permanente is the highest-performing healthcare organization in the U.S. for 71 care measures, including:

- Prevention and screening

- Respiratory care

- Comprehensive diabetes care

- Mental health

During this same period of healthcare improvement in which union members have been an integral part of, the unions have tripled in membership and have maintained the highest wages, benefits, and working conditions across the industry.

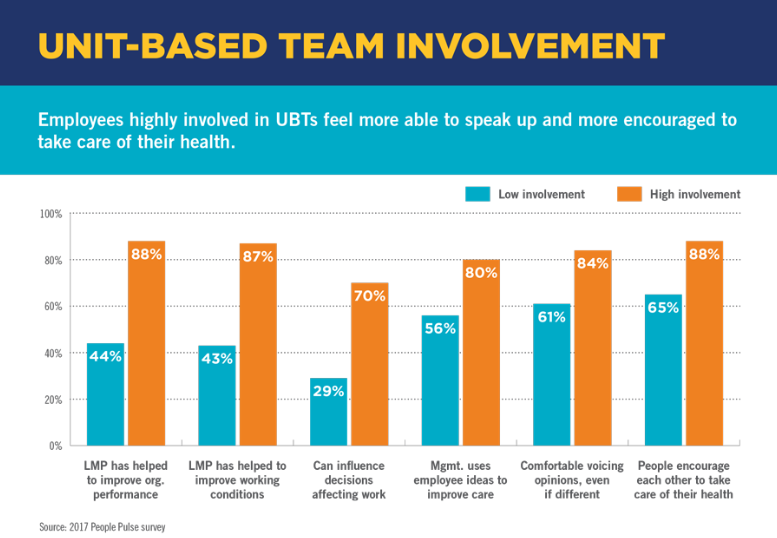

And while employee engagement in healthcare deteriorates, Kaiser Permanente employees have some of the highest engagement scores in the industry, driven by exactly what Press Ganey (most prominent tracker of employee engagement) suggests is the key to improvement: teamwork.

Here is an illustration of the relationship of employee participation in unit-based teams and improved engagement:

To appreciate the overall context of the significance of the LMP and its high performance, it is important to remind ourselves of the data behind the poor experience most Americans have with their healthcare:

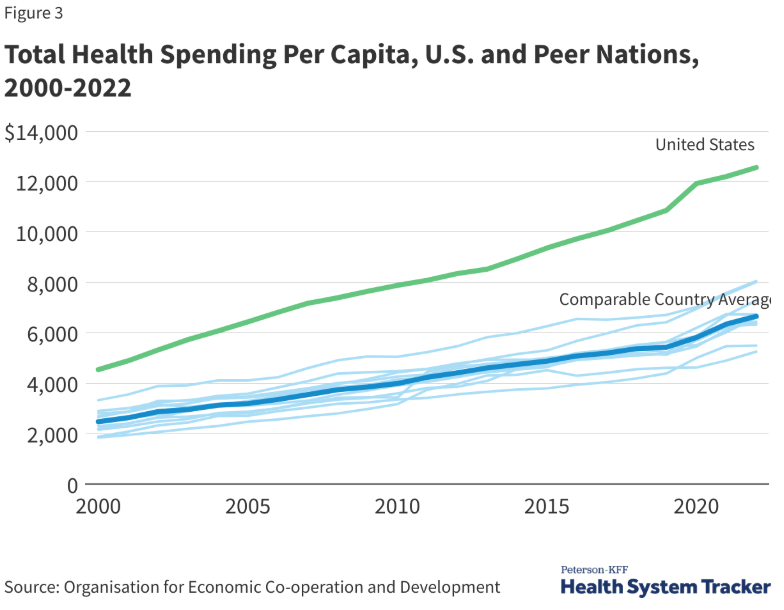

Over the years 2024-2033 average National Health Expenditure (NHE) growth (5.8 percent) is projected to outpace that of average Gross Domestic Product (GDP) growth (4.3 percent), resulting in an increase in the health spending share of GDP from 17.6 percent in 2023 to 20.3 percent in 2033.

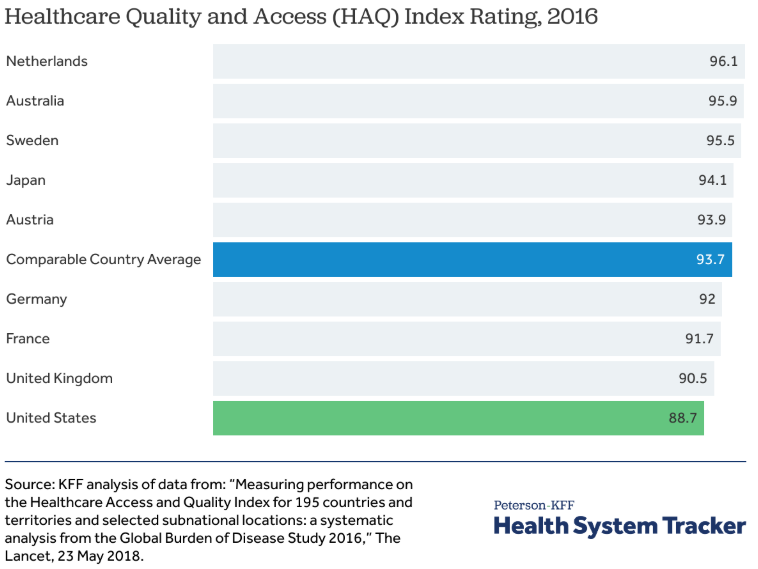

And…we don’t get what we pay for. The U.S. continues its highest spending on healthcare in the world contrasted with the poorest outcomes of other wealthy nations.

And so much of what is spent is wasteful:

- failure of care delivery, $102.4 billion to $165.7 billion;

- failure of care coordination, $27.2 billion to $78.2 billion;

- overtreatment or low-value care, $75.7 billion to $101.2 billion;

- pricing failure, $230.7 billion to $240.5 billion;

- fraud and abuse, $58.5 billion to $83.9 billion;

- and administrative complexity, $265.6 billion.

Estimated annual savings from eliminate waste were as follows:

- failure of care delivery, $44.4 billion to $97.3 billion;

- failure of care coordination, $29.6 billion to $38.2 billion;

- overtreatment or low-value care, $12.8 billion to $28.6 billion;

- pricing failure, $81.4 billion to $91.2 billion;

- and fraud and abuse, $22.8 billion to $30.8 billion.

The estimated total annual costs of waste were $760 billion to $935 billion and savings from interventions that address waste were $191 billion to $286 billion.

All health systems in the U.S. contribute to the above-defined disaster that is American healthcare. All health systems and their workforces experience the downstream impact in the workplace. Conflict ensues.

It should appear from the success of the Kaiser Permanente LMP and the suboptimal experience Americans face with their healthcare experience, that labor and management leaders in healthcare would choose the LMP as a model for a joint effort to contribute to a plan to improve healthcare for many more millions of patients outside of the Kaiser Permanente footprint. But that is decidedly not the case.

I have seen less interest in partnership experiments than I did 10-15 years ago when many efforts in healthcare were underway.

In many ways it is understandable. After all, prior to 1997, the unions and the leadership of Kaiser Permanente were locked in acrimonious labor relations and strikes. That acrimonious relationship was driven by external forces including increased competition.

Today the conditions in the industry are driving more intense conflict than perhaps ever before: very tight financial margins in increasingly powerful and consolidated health systems, workforce shortages, rapidly advancing technologies, including AI, and expected cuts in Medicare and Medicaid.

How can progress be made?

I am reminded of an experience I had about 10 years ago which is illustrative of the challenges and what to do to promote labor-management partnership at a time when it is needed more than ever: I participated on a panel at the Labor and Employment Relations Association (LERA) national meeting. Our panel presented on the successes of the Labor-Management Partnership at Kaiser Permanente (LMP). We received questions from the audience that asked us to further illustrate successes and the methods used to achieve the great outcomes across Kaiser Permanente, one of the largest health systems in the nation.

To this day, I remember Cornell-ILR Scheinman Institute Director, Harry Katz asking what I considered the most important question for our panel: “While the partnership is clearly a success, why do you think it is so difficult to build more of them around the country?” I tried to answer, but I think my answer was largely inadequate: I said that I believed the United States lacked a high degree of social solidarity unlike other countries where forms of labor-management cooperation were more highly developed.

Since that time, labor-management partnerships remain a very small portion of labor-management relations across the country.

I think a much better answer to Professor Katz’s question is that Labor-Management Partnerships are largely misunderstood, and that it appears today that it is increasingly difficult for labor and management to envision how a collaborative relationship meets the interests and goals of the respective parties.

For further understanding of this problem I share the following text from an article entitled, “Helping labor and management see and solve problems” by John R. Stepp, Robert P. Baker, and Jerome T. Barrett, from September 1982:

“Before any labor-management relationship can be improved, the parties to that relationship must both be dissatisfied with the status quo and have before them some blueprint which, if followed, has a reasonable chance of succeeding. In many cases, labor-management relationships are operating at a suboptimal level. This can happen for many reasons; for example, one or both sides prefer it that way, they are not prepared to incur the political or economic costs they attach to improvement, they do not know how to gain the necessary credibility to move jointly forward, or they simply do not know what to do.”

This is a clear and concise statement of why labor-management partnerships have not expanded.

John Stepp was a mentor to me. He taught me that “performance is a union issue.” That concept guided me in the years I had the privilege of leading the Kaiser Permanente unions in the LMP. I needed to understand that the LMP was not only for the purpose of improved labor relations, including creating conditions for less acrimonious bargaining and a reduction of grievances and conflict. I Iearned that organizational performance is wholly reliant on an engaged workforce, and that the measures of performance: quality, patient experience, affordability of care, and creating and maintaining the best place to work were jointly held interests by workers and management.

I learned that by taking a systems approach to healthcare improvement, the role of front-line workers was not just a matter of having higher engagement, but being active participants in the development of the systems of improvement resulted in their ownership of the improvement processes themselves.

Indeed, I saw that bargaining became less acrimonious and workplace conflict was reduced. More significantly, the parties saw their interests as mutually held because all activity of the organization was focused on improvements for patients.

Today there are 2 million healthcare workers who belong to unions. There is much conflict, but there is much potential for improvement if the workforces and their management and their unions followed the Kaiser Permanente model.

There are many hesitations from labor and management to venture forth…the challenges that the current state of affairs in healthcare presents overwhelming challenges and there is much conflict between the parties as a result.

It must be noted that outside of the unionized sector in healthcare and in some places within it, health systems are increasingly adopting the Toyota Production System (TPS), sometimes called “Lean Healthcare” and with substantial success.

Indeed, many of the process improvement practices in the Kaiser Permanente LMP utilize many of the principles of the TPS. We know from studying Lean implementation that there are many challenges, especially integration into heavily unionized settings. (For discussion in another article in this column). The performance improvement practices adopted by the workforce, managers, and physicians in the LMP were jointly developed and implemented. It occurred over time through the unique interest-based bargaining practices adopted by the parties. As a result, many of the obstacles that other organizations face when implementing process improvement, through the LMP, these obstacles were overcome.

This is an important part of the evolving story of whether or not and to what extent labor-management partnerships in the unionized sector will grow. Building understanding of labor-management partnership, therefore is essential

I am convinced that if the parties really understood the purpose and processes of labor-management partnership as experienced by the 200,000 union members, doctors, and managers and executives of Kaiser Permanente they would try. They would learn that the focus of the partnership is on the patient, a purpose all parties embrace every day, but do not necessarily have the systems in place to meet the patients’ needs.

Just like the nation as a whole.

John August is the Scheinman Institute’s Director of Healthcare and Partner Programs. His expertise in healthcare and labor relations spans 40 years. John previously served as the Executive Director of the Coalition of Kaiser Permanente Unions from April 2006 until July 2013. With revenues of 88 billion dollars and over 300,000 employees, Kaiser is one of the largest healthcare plans in the US. While serving as Executive Director of the Coalition, John was the co-chair of the Labor-Management Partnership at Kaiser Permanente, the largest, most complex, and most successful labor-management partnership in U.S. history. He also led the Coalition as chief negotiator in three successful rounds of National Bargaining in 2008, 2010, and 2012 on behalf of 100,000 members of the Coalition.