Understanding The Kaiser Permanente Labor Crisis

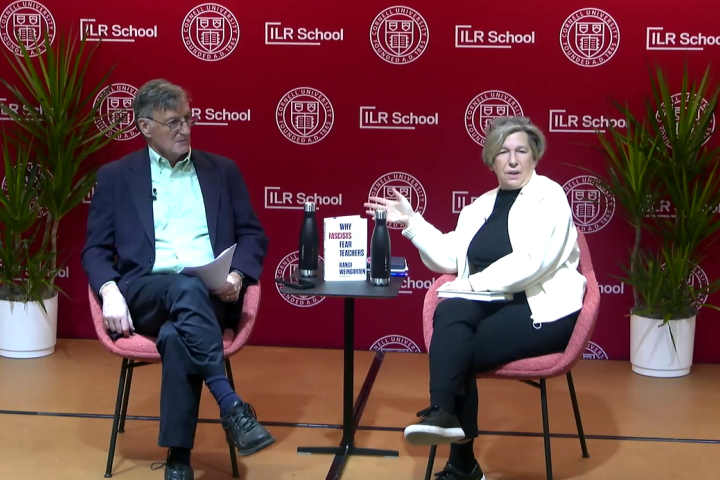

By John August, Director of Healthcare and Partners Programs at The Scheinman Institute

On November 13, 2021, just 48 hours before a strike deadline was to take effect by more than 30,000 Kaiser Permanente union members in California and Oregon, a settlement was reached to avert that strike. Had the strike not been averted, thousands more Kaiser Permanente union members were ready to join the strike in Hawaii, Colorado, metropolitan Washington, DC, and Georgia. It would have been the largest strike in the nation in the past 25 years, with nearly 50,000 union members on picket lines.

The union members involved in this dispute all belong to the Alliance of Healthcare Unions (AHCU) who are signatories to the Kaiser Permanente Labor Management Partnership (LMP).

After many months of negotiations, which commenced in April of 2021, it appeared that a strike would occur. The centerpiece of the dispute was the position taken by Kaiser Permanente that a two-tier wage system be implemented for new employees.

The unions mobilized for strike actions to commence on November 15, 2021. As that strike deadline approached, the Kaiser Permanente bargaining positions began to soften, and on November 13th, a tentative agreement was reached.

KP dropped its position for a two tier wage system and agreed to many of the union proposals, a summary of which includes:

- Common Annual Wage Increases across the country with NO Two-Tier for New Hires: The same annual wage increases for all members, regardless of region or date of hire! These raises are effective on October 1st of the following years: 3% 2021; 3% 2022; 2% + 2% bonus 2023; 2% + 2% bonus 2024.

- Better staffing, budgeting and backfill agreements: Regional labor management staffing committees will meet monthly to discuss a broad range of specific topics. There will be monthly discussions with labor about vacant or modified positions and backfill strategies at the unit or department level, as well as reports about the status of filling vacancies. Labor and management will collaborate to develop strategies to address hard to fill positions and reduce the use of travelers and non-bargaining unit temporary employees. Unions will get monthly reports about patient satisfaction and access.

- Wage justice: Members of the USW and Teamsters in the Inland Empire, and certain members of the UFCW in Kern County, have historically been paid on a lower, sub-regional wage scale. Alliance unions resolved that in this round of bargaining, they would unite to ensure that they begin to rectify this long-standing disparity. Under the TA, the affected unions and management will meet to decide how to make progress by distributing amongst the affected jobs 1.25% of payroll, beginning on July 1, 2022; and another 1.25% of payroll on July 1, 2023. These improvements will make significant progress towards equity.

- The racial justice bargaining subcommittee also agreed on implementing processes and programs such as Belong@KP to address racial trauma/fatigue, and funding citizenship assistance.

- Fair contracts for new union members: Newly organized members of UNAC/UHCP in NCAL and Hawaii, and of UFCW Local 21 in Washington, worked ceaselessly to secure first contracts with KP and achieved them with 52,000 Alliance members standing behind them in solidarity.

- Align benefits to national standard: Continuing a long-time commitment to equal benefits for all Alliance members, local union benefits will be closer to the Alliance national standards in areas where they lag. Retiree medical for KP Washington members increases from $350 per year of service to $1,000 per year of service. Mid-Atlantic union members got a big decrease in out-of-pocket maximums. In Hawaii copays will be lowered from $15 to $10.

- More money for Ben Hudnall educational fund: An additional $15 million for Ben Hudnall Memorial Trust to protect educational benefits and advance careers.

- Local bargaining gains: Many local unions also won significant improvements to their local contracts.

It appears to this observer that the Alliance Unions prevailed in this dispute. Clearly the power of a demonstrated, prepared and unified group of tens of thousands of workers who have been on the frontlines of the COVID-19 pandemic, showed extraordinary power to stop the two-tier wage threat and win on many of their demands.

It is also very interesting and important to note that in addition, the following agreements indicate joint work that reflects strong elements of the Labor Management Partnership, including:

- Preserve the Performing Sharing Program (PSP) with increased focus on affordability: One element of partnership is making health care more affordable in order to increase access to health care. As part of this new agreement, the Performance Sharing Program (PSP) will be kept intact, and two-thirds of the annual bonus will be tied to joint initiatives for cost saving, beginning in 2023.

- Joint Affordability Task Force: In accordance with the original vision of partnership, unions and management will work together to find ways to reduce overall costs—with mutual agreement required to implement.

These two agreements reflect a long standing joint perspective held by management and labor: that central to the LMP is commitment to continuous improvement in cost savings without reducing workers’ wages, benefits, and working conditions. These agreements ought to serve as a healing process after the near-strike.

- Patient and worker safety: The subcommittee on patient and worker safety reached consensus on adding language to the National Agreement on Just Culture, a recognition program for reporting of near misses, identifying and developing a communication process for emergency preparedness, and updating prevention of workplace violence. The group also recommended creation of a National Health, Safety and Well-Being Committee to ensure that Just Culture and Psychological Safety are integrated into current work streams.

- Better, faster resolution of disputes: Resolving disputes in a timely manner has been a partnership challenge. The new language replaces several processes with a single, improved process to resolve disputes faster with improved partnership and fact-finding. There will be guidelines and training for all parties. (List of elements of the Tentative Agreement documented from the Alliance of Healthcare Unions website, Alliance of Health Care Unions (ahcunions.org)

Even though a tentative agreement was reached with the Alliance Unions, sympathy strikes did occur on November 15th in northern California as several unions did walk off the job for a day in support of 700 members of the Operating Engineers Local 39 who have been on strike over pension benefits for two months. Local 39 is not a participant in the LMP. One of those Unions, SEIU-UHW is part of the Labor Management Partnership, though part of a rival Coalition of Unions to the Alliance of Unions referred to above, while the others, the CNA and NUHW are not part of the LMP.

A settlement was reached with yet another union, not part of the LMP, the Pharmacists Guild.

Combining the sympathy strikes by thousands of workers and the near-strike by tens of thousands more, the costs of preparations for these strikes, not to mention the strain in labor relations was extreme.

What makes the labor strife at Kaiser Permanente uniquely relevant to understand?

It is very important to try to understand why these events occurred and what the future holds for the “largest, most complex and most successful Labor-Management Partnership in U.S. history”. (The Kaiser Permanente Labor Management Partnership, 2009-2013, Thomas A. Kochan, Institute for Work and Employment Research, MIT Sloan School, September, 2013)

It is necessary to differentiate the near- strike at Kaiser Permanente from the current strike wave and other expressions of worker activism underway across the nation. This threatened strike arrived at a critical moment in the history of both healthcare and Unions, and there is much to learn from a possible strike among tens of thousands of workers who are participants in a nearly 25 year history of labor-management partnership, in part designed to avoid work stoppages.

For the past year or more, the daily news has been full of strikes and threatened strikes on a scale we have not seen in the nation for many years. “There have been some 185 strikes at 255 locations this year, with at least 40 occurring in October, according to the Cornell University School of Industrial and Labor Relations' tracker. The researchers behind the tracker define a strike as a "temporary stoppage of work by a group of workers in order to express a grievance or to enforce a demand that may or may not be workplace-related."

Among the most prominent is the recent strike of 10,000 John Deere workers across more than a dozen plants that are represented by the United Auto Workers. Some 1,400 workers represented by the Bakery, Confectionery, Tobacco Workers and Grain Millers International Union are also on strike at Kellogg's plants across four states. (ABC, Good Morning America, October 22, 2021.)

Other on-going and long strikes include 1100 United Mineworkers of America coal miners at Warrior Met in Alabama who have been out since April. The strike by 600 RNs at St. Vincent Hospital in Worcester, MA is approaching eight months in length. A month-long strike by 200 RNs at Mercy Hospital in Buffalo, NY settled just a month ago.

In addition to strikes, the nation is experiencing what NY Times Opinion columnist Paul Krugman calls “the Great Resignation”: “America is a rich country that treats many of its workers remarkably badly. Wages are often low; adjusted for inflation, the typical male worker earned virtually no more in 2019 than his counterpart did 40 years earlier. Hours are long: America is a “no-vacation nation,” offering far less time off than other advanced countries. Work is also unstable, with many low-wage workers — and nonwhite workers in particular — subject to unpredictable fluctuations in working hours that can wreak havoc on family life.” Krugman adds, “Workers are quitting their jobs at unprecedented rates, a sign that they’re confident about finding new jobs. On the other side, employers aren’t just whining about labor shortages, they’re trying to attract workers with pay increases.” (NY Times, October 14, 2021)

Rising inflation, rising expectations for better wages and working conditions, and the impact of a decades-long period of stagnation in wages all exposed by the pandemic are central and consistent reasons given for the wave of strikes, as well as what could be viewed as the largest strike in U.S. history as millions of workers are refusing to take jobs that are open or are quitting jobs they have!

Squarely in the mix of this wave of union and workers’ action was the threatened strike by more than 30,000 health care workers at Kaiser Permanente, the largest unionized health system in the nation, with about 75% of its 220,000 employees belonging to unions.

These unions, which include RNs, technicians, clerical, and all manner of ancillary personnel, are part of the Alliance of Healthcare Unions, one of two major union groups who are part of the LMP. These unions number 48,000.

There is another major union group that is signatory to the LMP. That is the Coalition of Kaiser Permanente Unions, dominated by local unions of SEIU, which represents 85,000 workers across the nation in Kaiser hospitals and clinics. This Coalition will be in contract renewal talks in 2022. The Unions of the Coalition had circulated petitions of support for their co-workers in the Alliance.

A Distinction with a Difference

What stands out in the Alliance-Kaiser dispute that is different from the rest of the strikes and activism going on in the present moment?

More than twenty-five years ago, writing in the Transformation of American Industrial Relations (ILR Press, 1994) scholars Harry Katz (Director of the Scheinman Institute), Thomas Kochan, and Robert McKersie framed the state of labor-management relations: “The traditional New Deal system of collective bargaining was undergoing significant changes that were both necessary to its future viability and yet at risk for lack of supportive public policy.” This group of scholars continued to study and was directly involved in partnerships in steel, clothing, telecommunications, and other industries. They and others studied the most ambitious labor-management experiment of the era by General Motors and the UAW at Saturn.

None of these previous attempts at partnership and innovation in labor relations and efforts to achieve high performing work organizations turned out to be sustainable even though each of them achieved positive results in the short term.

Today, only the LMP at Kaiser Permanente remains as a continuous effort in labor-management innovation with a single major employer on a very large scale.

At the same time today, the private sector unionized workforce in the U.S. hovers just above 5%, and only 11% of the workforce overall. Whether or not and in what forms a resurgence of unions will take place remains very open questions.

Yet over the 25 years of the LMP at Kaiser Permanente, most observers agree, that a model for at least some aspects of a new and innovative labor-management relationship was showing success. Some of those characteristics of innovation include:

- Empowerment of all frontline staff (nurses, doctors, technicians, clerical, IT, aides, dietary, environmental, and transport workers) to be active participants in problem-solving with attention paid to mutual gain and continuous patient-centered performance improvement

- Elimination of employer opposition to union organizing among non-union workers

- Steady growth of the enterprise and the unions

- Continuous improvement of wages and benefits built upon what is considered as the highest level of wages, benefits, and conditions in the health care industry

- Employment security

- Use of alternative dispute resolution practices such as interest based bargaining and issue resolution/corrective action

Moreover, many observers also agree that the size, scale, and success of Kaiser Permanente as a health system could be the model for the nation:

“When people talk about the future of health care, Kaiser Permanente is often the model they have in mind. The organization, which combines a nonprofit insurance plan with its own hospitals and clinics, is the kind of holistic health system that President Obama’s health care law encourages.

Kaiser has sophisticated electronic records and computer systems that — after 10 years and $30 billion in technology spending — have led to better-coordinated patient care, another goal of the president. And because the plan is paid a fixed amount for medical care per member, there is a strong financial incentive to keep people healthy and out of the hospital; the same goal of the hundreds of accountable care organizations now being created

Over the course of the last 15 years, they’ve been just going into high gear and doing everything right,” said Dr. Thomas S. Bodenheimer, a health policy expert at the University of California, San Francisco, who recently chose Kaiser as his own health plan.”, (“The Face of Future Healthcare”, New York Times, March 20, 2013).

Today, Kaiser Permanente has 12.5 million subscribers and operates in California, Oregon, Washington State, Hawaii, Colorado, Georgia, and in metro Washington, DC. It is the largest not-for-profit health plan in the nation and consistently receives the highest ratings from Medicare as the top health plan in the nation.

A True Crossroads

“To us, the central intellectual question in this project was whether the partnership the parties were building would yield the organizational performance results for workers, unions, Kaiser as an employer, and for the members/patients that Kaiser served”. (From “Healing Together”, Kochan, Eaton, McKersie, Adler, Cornell University Press, 2009, p. 6). “Healing Together”, along with the updated study of the LMP at Kaiser referenced earlier in the 2013 monograph by Kochan remain the only definitive studies of the LMP. This question posed by the authors, remains the central question that should be asked at this moment as a large segment of the workforce barely avoided a major strike.

Here then are some questions and perspectives to keep in mind as we reflect on the labor crisis at Kaiser Permanente. We know from experience that even near-strikes take a long time to get beyond. The LMP rests on trust and collaborative strategizing for success, challenging operational work under the best of circumstances.

The LMP was formed out of crisis. Responding to years of lay-offs and staffing issues through the 1980s and 1990s, most of which were motivated by the external forces of newly emerging trends in prospective payment systems, new technology, and for-profit competition, the many unions of Kaiser Permanente which had historically bargained as individual local unions formed a coalition. That first-time the coalition began organizing for the first national strike supported by a corporate campaign to support its demands. The strike was set to commence in 1997.

The leaders of both Kaiser Permanente, Dr. David Lawrence and the President of the AFL-CIO, John Sweeney at the urging of members of their constituencies, sought a means to avoid what all agreed could be a catastrophic outcome of a national strike: They decided to form a Labor-Management Partnership. Central agreements in the original 1997 LMP Agreement remain today in the union contracts and Partnership Agreement, reaffirmed several times. These agreements include:

“Health care services and the institutions that provide them are undergoing rapid change. Advances in health care and the explosive growth of for-profit health care businesses present challenges as well as opportunities for Kaiser Permanente, the unions, and the members they represent. Kaiser Permanente and the undersigned labor organizations believe that now is the time to enter into a new way of doing business. Now is the time to unite around our common purposes and work together to most effectively deliver high quality health care and prevail in our new, highly competitive environment. As social benefit membership organizations, founded on the principle of making life better for those we serve, it is our common goal to make Kaiser Permanente the pre-eminent deliverer of health care in the United States. It is further our goal to demonstrate by any measure that labor-management collaboration produces superior health care outcomes, market leading competitive performance, and a superior workplace for Kaiser Permanente employees.”

1.) There is a long history both internal to Kaiser Permanente and its relations with its unions where conflict has been resolved and advanced the organization’s success:

a. In 1945, when the Kaiser Shipyards closed and the large majority of unionized workers left to return to previous jobs held after the end of World War II, the new Kaiser Health Plan was near collapse. It was the unions, led by the ILWU who asked Kaiser to open the health plan to the public and committed union members to join the Plan. Thus began the stability and growth of what became Kaiser Permanente.

b. In the 1950’s when Permanente doctors and leaders were attacked by the AMA as promoting “socialized medicine”, it was the unions who came to their defense at the height of the McCarthy period.

c. In 1996-1997 when on-going conflict between the Permanente doctors and the Kaiser Health Plan nearly destroyed the enterprise, leaders from both parties came together and created the Kaiser Permanente Partnership Group (KPPG). This entity for the first time created joint leadership between doctors and health plan leaders, thus advancing the integration of services so central to the success of the organization. This unification of leadership also made the LMP with labor partners viable as all leaders of labor, health plan, and doctors came together in a joint effort to advance their mutual interests.

d. In 2000, national bargaining took place for the first time between all the many unions (26 local unions in 8 national unions) and the first national union contract came into being which codified the Partnership Agreement goals to achieve high performance and employment security

2.) Can the parties overcome a new and building set of challenges and divisions that have now created the conditions for the kind of conflict that existed PRIOR to the formation of the LMP in 1997?

a. It has always been the case, and an on-going challenge that Kaiser must confront how to be successful with both higher fixed costs and higher labor cost than competitors. None of this is new. Unlike its health plan competitors who do not operate hospitals and clinics, and who by and large do not have unions, Kaiser has always had to face higher costs than its competition. In fact the very business model of Kaiser and the cause of its success has been its ability to fully integrate its hospitals, clinics, medical providers, and insurance programs under one system. In doing so, it is able to carry out its model of pre-paid, preventive health care, the primary differentiator between Kaiser and its competition. Moreover, its relations with its unions are also central to its history and success as shown earlier. Having been unionized since its inception, collective bargaining has created higher wages, benefits and conditions than other health care systems in its markets.

b. Pressures to keep its costs under control have been a constant over the many decades and always created a kind of shadow over collective bargaining. Also, there is nothing new in this round of bargaining in 2021.

c. Over the 25 years of the LMP, much has changed internally:

i. Four changes in CEO

ii. New members of the Boards of Directors

iii. New leadership among the physician groups

iv. New leadership in labor relations and human resources

v. New leadership in most of the unions

vi. Factional/internal splits among the unions have developed. Through most of this period, all the major unions with the exception of the CNA operated as one Coalition. In 2018, approximately 48,000 union members formed the Alliance of Health Care Unions. Remaining in the Coalition of unions are 85,000 other workers. Each Coalition bargains separately with KP on different annual cycles.

In addition to the CNA, which represents 20,000 RNs, the National Union of Healthcare Workers (all former members of the Coalition) represents several thousand others, as do the IUOE Local 39 craft workers and bio- medical techs. Each of these unions bargains separately with Kaiser.

My observation is that Kaiser Permanente leadership views the divisions within the unions of the LMP, as well as the fact that several other strong unions are outside the LMP, with a “divide and conquer” perspective to achieve its bargaining goals which include reductions in wages and benefits. As just observed in the recent situation, the unions clearly have the power to threaten massive work stoppages in response. As such, it would appear that the unions still hold an upper hand based on this power, albeit a divided power.

This was true in 1997 when the LMP was formed. The LMP was formed to avoid these types of massive confrontations in the mutually understood and agreed interests of advancing the best model of healthcare jobs in the nation at the premier provider of healthcare in the nation.

The founding of the LMP was seen as a radical departure from traditional labor relations. It was seen then, as with its many predecessors in labor-management partnership as a necessary innovation in the face of the decade’s long erosion of labor-management relations, labor union membership, and a largely stagnant wage for most American workers.

In summarizing the history and conditions that the parties find themselves in at this moment in the immediate aftermath of a near national strike by nearly 50,000 workers, here are some reflections:

- Can this moment be seen as the same kind of existential moment that created the LMP out of a period of crisis in 1997?

- Can the parties recognize that there is overriding deep mutual interest in continuing efforts at achieving high performance while maintaining and improving what is “the best place to work” in the industry?

- Can the parties fulfill the hopes of a nation to create the high quality, affordable health system model that we need so badly?

- Can the parties continue to more fully advance and empower its frontline staff, doctors and managers to truly focus their efforts at unit based improvement and develop mutually committed daily work systems to eliminate all waste and keep costs in check without impacting the kind of wages and benefits that all workers deserve?

- Can leadership change and disunity give way to the kind of unity of spirit and mutual interest that has enabled the proven ability to meet the challenges of the past and advance this great model of health care and great conditions and voice for the workforce?

- Can the unions re-unify and with their combined and enormous power, forge the most successful LMP based on high performance and affordability for patients while enhancing the best health care jobs in the nation?

- Can the LMP sustain where other efforts have not?

To be able to answer these and other questions in the affirmative will go a long way toward answering the larger questions cited at the beginning of this article: Can there be sustained new forms of collective bargaining at a time when American labor relations is at such a pivotal moment and in need of deeply transformed organizational engagement?

Can the parties recognize that both internal and external forces are and will always continue as profound stressors on the ability of the organizations to succeed in their missions?

Perhaps this crisis, like so many others of the past, can lead to positive change.